By Joel Simon

I’m what some people call a Cedar Rat. I live alone with a couple of dogs in the Southwest high desert on less than $30 a week. I built my home and make my living largely on what other people cast off.

And this is my back yard.

I’ve been a hermit out here a long time now. My reasons don’t matter and would be far too long a story anyway. If I’d waited until I had the money and circumstances to do it right, I’d still be waiting. So finally I just did it.

I have no money, no safety net, no property, no credit, no bank account, no licenses or Government-Issued Photo ID of any kind. Haven’t owned a new shirt in a decade. I thought I might freeze a couple of times, and I sure learned to eat cheap.

For the first year and a half I had a job in a repair shop in the nearest town, fixing small engines. I met a lot of people as I fixed their chain saws, generators, and water pumps. The money was useful, but mostly it taught me about the sort of people who live in the desert, about their tools, their attitudes, and their outlook. What had been a theoretical life became a real possibility.

Some of these people were sun-soaked crackpots, some were drug-addled fools who may not even still be alive, and some were perfectly normal folks who just lived more simply and basically than I ever had. Without really meaning to, they showed me that an eight-to-five job wasn’t absolutely necessary for life — in fact, you can accomplish quite a lot by gathering resources in other ways if you just keep your eyes open for possibilities.

Of course, everybody needs some cash money. For several years I’ve earned $30 a week by helping some horse-raising neighbors with chores they’d rather not do. Yes, I’m an Equine Excrement Engineer. I’ve occasionally thought of having business cards printed up just for laughs.

Now and then, other cash jobs come my way, but mostly I work for barter. That has cut down my need for cash remarkably. For example, my two dogs are fed on good-quality sack food from the city, brought up by a lady who needs somebody to watch over her property and chickens. I also keep her Jeep running, which incidentally gives me wheels between chores, and I get my hens from her. When she needs cock birds slaughtered, I do it for a share of the birds. I swap labor for all sorts of things: building materials, surplus food and clothing, nearly everything in my solar power system, water rights, even the property where my cabin is built.

Which brings me to the first and probably the most important principle for living simply on the cheap:

Be a good neighbor.

Being a hermit doesn’t have to mean being completely misanthropic. In a space of about four square miles, the core of my range, I have about 12 neighbors (though most don’t live here full-time). Those relationships are essential to me, and they weren’t built in a day. It’s not always easy for people who live more conventionally to see that old bearded hermit as anything but a potential threat. But the sort of people who are drawn to build out here, even if they don’t plan to live here full-time, also tend to be open-minded about such things. And those who only weekend here or use their property as a vacation spot quickly find it’s useful to have somebody trustworthy around who can keep an eye on things. Those who are building — and there are always building projects going on — often need an extra set of hands. I keep available for that, and make it clear I don’t really want cash. Which brings me to the second vital principle:

People throw away the darnedest things.

I live in a 200-square-foot cabin. The dogs take up quite a lot of room and so does the bathroom and wood stove, but there’s still space for a cabinet, comfy chair, and a nice desk, all in fine condition. Up in my sleeping loft I’ve got a bed, a chair, and two dressers. I rescued each piece of furniture on its way to the county dump. People are always surprised by how cold it gets in the high desert — I certainly was — but I dress nice and warm in winter, and not in rags. At first I bought clothes from thrift stores, but I don’t even need to do that anymore. Not long ago, a neighbor changed his diet and wanted to ditch a lot of luxury food he’d stored but could no longer eat. Me, I eat almost anything. Point is, I keep handy and people keep me in mind.

It is vitally important not to abuse this. Early on, I used to muse that there might be a fine line between scrounge and steal but it’s really not that arcane. I know of properties with lots of valuable stuff lying around, just going to waste, owned by people who never seem to come back and with whom I have no relationship. I never touch it. As for the people I do know, they know perfectly well I’d never touch a pin belonging to any of them without permission. Actually, I’ve got keys to most of the untenanted buildings around here, because sometimes the owners need somebody to go in and check on things, or let workmen in, or something like that. Those people never come up missing anything. And if somebody wants me to keep an eye on his property and discourage unauthorized visitors, they know they can trust me for that as well.

The result of that is goodwill, built up over years. And so when those same people have something they’d rather I did haul off, they let me know what it is.

That’s the way I get about fifty percent of my firewood, by the way. One problem with heating with wood in the desert is the lack of trees. We have a lot of juniper, of which one friend said, “That’s not a tree. That’s a bush with delusions of grandeur.” The advantage of juniper is that it lives for centuries — some say thousands of years, but I don’t know — by dying in parts and growing new parts. So you can cut as much as you need without ever hurting a tree. The disadvantages are several. It’s dirty wood, dirt gets stuck right in the wood as it grows, and it’s really hard on saw chains. Much of it is just brush, so there’s a lot of waste getting to the good wood. And it doesn’t burn very hot: If you’re not careful, you can get a lot of creosote in your stovepipe. So I make a standing offer to everybody who lives around me: If you ever want to get rid of any pallets, let me know and I’ll haul them off promptly for free. You can build things with pallets and sometimes I use the best ones for that, but mostly I tear them up for firewood. The same is true for old sheds and such that need to be torn down and hauled off; if I can’t use it for building materials, I cut it to stove lengths.

Access to tools

When you live far back in the desert, you need to know your tools will work so sometimes it’s worthwhile to scrimp on other things instead. Even though I have very little money, I learned early that most of the time it’s best not to bother with cheap tools. That doesn’t always mean paying full price at a hardware store, though. The fellow I used to work for in town got a gently used older Husqvarna chain saw in on consignment. He knew I was wanting a good saw, gave me a call, and let me pay for it in installments. I treat it well, keep my chains sharp, and it’s on its fourth winter without any problems.

I never go near the pallets with it, though. You can never be sure you’ve pulled all the nails from a pallet, and nails are death to expensive chains and maybe even the bar. So on pallets, I use an electric reciprocating saw with easily-replaced blades. I found an old Milwaukee Sawzall in a thrift store, and it does a fine job on wrecking work. I just need to bring the wood to where there’s electricity.

My basic hand tools aren’t the most expensive you can buy, but I don’t get them from a dollar bin. And though in other ways I’m not the most fastidious person you’ll ever meet, I take care of my tools. My power shed has a place for everything, and I try to make sure everything is in its place. Not long ago, a pack rat moved into the shed. It wasn’t getting into my food, so I let it be, and that was a mistake. One evening I neglected to close the lid on my toolbox, and that rat stole about half my sockets. I had to pull a lot of heavy things out of the shed to tear out its big nest and get them back. And then I set traps and sent that rat to rodent heaven.

Which brings me to the possibly unpleasant subject of:

Carry your weapons

Several years ago, I killed a badger my dogs had picked a fight with. A city fellow heard the story and was horrified that I would do such a thing, since technically it was all the dogs’ fault. Why kill the innocent badger?

“I’m responsible for the dogs’ welfare,” I told him, “and not for that of the badger.”

I tried to explain, though I don’t think he ever accepted it, that we don’t live in a park here. This is wild country. We have rattlesnakes, coyotes, government-introduced wolves, mountain lions, and feral dogs. Mostly, with a little care, the animals are no threat to me. I need to watch out for my own animals, though. The dogs (and hardened coops) mostly keep the coyotes away from the chickens, but one time when my boys happened to be elsewhere, I came out of my cabin to find a very surprised coyote in my yard, visiting my hens. I guess she figured that if the dogs were gone, I was, too. That’s usually so. We had a short, loud discussion about that and it never happened again.

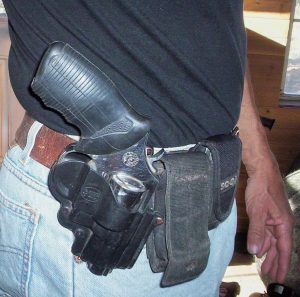

It happens rarely, but it happens and it never calls ahead for a reservation. And that’s why I’m always armed. I keep a carbine loaded on my wall, but never seem to have it with me when trouble calls. There was an incident with a dog pack that mauled a neighbor’s cow, and then the carbine came down off the wall. But mostly the need comes as a surprise.

The pistol is always there. When I was younger, I used to compete with a 1911 .45, and I’m of the geezer generation that thinks it’s the only proper pistol to carry. But all my experience was with paper targets; I’d never actually used one to stop a fight. Maybe they’re fine for bigger animals like bad guys, but that isn’t what I need to shoot at out here. After a few through-and-through hits on smaller creatures with round-nose .45 bullets that failed to stop the fight — the last one a Mojave Green rattler that picked a fight with me, and that my .45 only seemed to make more angry — I decided I wanted bigger cartridges and yawning, cavernous hollow-point bullets. So I traded some labor for a beater .44 revolver. It needed a good cleaning and a few new parts, but it works fine now.

Mind you, I’m not Rambo. I don’t even hunt much. But I’m not in a position to call 911 when there’s trouble. The dogs are useful: They warn off the other animals, and when that doesn’t work, they warn me. And then they usually get behind me. The dogs hold me responsible for quarters, rations, weather, and firepower.

Always know where your food is coming from — lots of food — and what to do with it.

When I was little, there seemed to be an assumption that I’d never have to cook. When I was married, I wasn’t really even welcome in the kitchen. Later, while I could afford it, I ate in restaurants or out of packages. Came a time when I couldn’t afford it, and I didn’t even know how to cook rice. There was a painful learning curve.

But that was a long time ago. While nobody’s going to offer me a cooking show anytime soon, I can at least cook palatable food. At this high altitude, boiling some things doesn’t get it done, so I learned how to use a pressure cooker. I learned how to hunt and to raise chickens. One of these days, I’ll try my hand at raising rabbits, since I find wild rabbits hardly worth the bother. Always did like chicken, though.

I try to keep a lot of flour on hand, because I bake all my own bread. Potatoes and onions are cheap, and I gradually learned what to do with spices. The hens give me as many eggs as I can eat as well as some to trade. I don’t use much canned goods.

I don’t mind shooting animals from a respectful distance, but one of the hardest things was raising animals and then killing them up close and personal. As I suppose it is with most people not raised on farms, I always figured an animal you raise yourself is a pet. You’re not supposed to kill it, and certainly not with a hatchet. I got over that. As I said, I do enjoy eating chicken, and nobody’s going to come and slaughter them for me.

Since I never know when I’m going to have a financial dry spell, I store a lot of basic food. Having learned how to cook, I can get by for a long time on my bulk commodities. I store flour, beans, rice, oatmeal, sugar, barley, and salt in bulk.

Just as important as storing lots of bulk food against lean times is keeping it away from rodents. At first I made some expensive mistakes, because we’ve got millions of rats and mice and ground squirrels that seem to think I live to feed them. But food-grade buckets are your friends. I can’t keep the rats out of my shed, but they’ve never successfully gnawed through one of my buckets.

The buckets themselves are inexpensive, bought online. The spin-on lids are expensive, but worth it, and I’ve never seen one wear out. A single bucket holds about 20 pounds of rough-cut oatmeal or 30 pounds of flour, so it’s easy to keep track of how much you’re using and how much you have left. I don’t ever like to run low, but sometimes local supplies dry up for a time. So it’s good to have a lot on hand. Then when it comes on sale, you fill your buckets. If I watch the sales, I can get 100 pounds of good quality flour for $40. Mostly I use commercial dry yeast for bread, storing most of it in a neighbor’s freezer. But I’ve experimented with sourdough starter and can do that if I need to.

Keeping stuff clean

As I said, I dress pretty well for a guy without a regular job. But this is a dirty place where I spend a certain amount of time up to my knees in mud and horse manure, and keeping my clothes clean was another learning experience. Once I stopped going to town every day, I gradually dropped the habit of going there very much at all, so laundromats were out, and I certainly didn’t have enough electricity to run a washing machine. So I had to learn to do it myself.

Weather permitting, this is the best system I’ve come up with. I started with six-gallon buckets but that proved too limiting. Full-size garbage cans are too heavy, but ten-gallon tubs are just right. Washing goes in one, rinsing in the other, and after a spray and a wringing, it all goes on lines strung between the junipers. The hand agitator works quite well. It was a gift from a friend who saw me doing it with a toilet plunger.

Be prepared to adjust your expectations.

I had an awful lot to learn when I moved out here, but there’s an advantage to living in an area with lots of poor people: The local economy is geared to serve them. Good-quality food and baking stuff are available cheap. I’ve read about people who cry poverty and claim they can only afford to eat fast food. There are still real poor people in this country, and for them a fast food meal might be a twice-a-year indulgence. In fact, the nearest drive-through is 40 miles away. Poor they may be, but some of them may eat better than you because they know how to use what they have.

For the first several winters in the high desert, I lived in an old RV trailer. Its walls contained no more than a homeopathic dose of insulation. The furnace needed both propane and electricity to run, a ridiculous arrangement, and it died entirely in the middle of the second winter. Nighttime temperatures here routinely go into the teens, and often quite a bit lower. I really thought I might freeze to death a couple of times.

I never did, of course. What I did was get over it. Whining wasn’t helping my situation at all. I found ways to heat that little trailer as best I could, and piled on layers.

Meanwhile, with the occasional help of some friends, I got busy building a proper cabin. Gathering materials took years. All the linear lumber was salvaged, and I spent many hours pulling nails. I got odd jobs to pay for the sheathing and roofing. The windows and door came from a salvage yard. I couldn’t gather all the fiberglass insulation I needed, but a storage business in a nearby town got stuck with a whole unit full of old clothing someone had abandoned. I do believe if I were a better negotiator they’d have paid me to haul it away. As it was I bought the whole lot for $25. Rolled up loosely, that went into my 2×6 walls for insulation.

The fellow on whose land my cabin is built had a well dug on the high ridge between my place and his own. I helped put in the pump, tank, lines, and electrical, and he allowed me to tap into it.

A friend with a backhoe helped me trench down the hillside, about 400 feet. It didn’t cost me anything but the diesel fuel. Once I’d saved up for the flexible pipe and some fittings, I had running water!

That made an actual flush toilet possible, an incredible luxury — after I’d dug a septic system. More time spent finding salvaged plumbing materials! It took weeks just to scrounge the gravel I needed for the leach field. In fact, the water project set my move-in date back enough that I had to spend another winter in the trailer, but it was worth it.

Learn to raise poultry.

A neighbor decided to try her hand at raising chickens, and needed my help because I’m here full-time and she isn’t. Personally I thought it was a fool’s errand at first. Why go to all that trouble just to feed the coyotes? But I’d pretty much decided wild rabbits weren’t worth the trouble for what little meat they provided, my diet had become almost entirely vegetarian and awfully monotonous, and I wanted some animal protein. So I got involved. Now we keep two little flocks in hardened coops and runs.

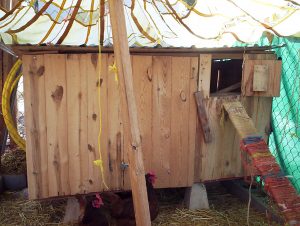

With fence rails sunk in a foundation of concrete-filled blocks, then wrapped in scavenged chain link fence, the Fortress of Attitude has given safe haven to two generations of Rhode Island Reds now. Baling twine and an old cargo parachute gives top cover from hard sun, and also from hawks and owls. We’ve got owls out here that ought to have Lockheed logos on their wings — they routinely kill cats, but they’ve never gotten one of my chickens. Coyotes have sniffed around it but never penetrated, and we’re thankfully low on smaller predators. The dogs mostly keep the coyotes honest, but the only one I ever shot was right around here.

I practice deep-litter composting which keeps the smell down, gives the girls something to do, and also cuts down on feed cost. All my kitchen trimmings go in here. What the chickens don’t eat attracts bugs, which the chickens eat. I’ve also seen them squabble over the torn carcass of an occasional mouse.

Their coop was also made from salvage. During summer, I clean it out daily. During winter, I spread straw and let the litter accumulate. Gives them a little protection from the cold, though Rhode Island Reds have proven very hardy. On summer afternoons, they often nap under the coop.

But what about emergencies?

Obviously there are contingencies nobody can face on $30 a week. I’ve had a couple of health issues since moving here. One I could deal with by paying in installments, but the other would have been a disaster without the kindness of friends.

In 2013, my eyesight, which was never very good, started going all to bits. I figured I needed new glasses so I saved some money and caught a ride to the big town about 50 miles away for an appointment with an optometrist. She examined my eyes, turned white as a sheet, and said I could save my money on glasses. The glaucoma, she said, was almost as bad as the cataracts.

On my own resources I couldn’t afford to deal with either of those things, but I sure didn’t want to go blind. Neighbors helped me with regular rides to the big town for ophthalmologist appointments. And then readers of my blog, joelsgulch.com, kindly raised thousands of dollars for the regular glaucoma medicine and the cataract surgery. Now I’ve got new lens implants, and see better than I ever did.

Gardening, not so much

Every spring, I try my hand at gardening. It gets ever more elaborate, with raised beds and store-bought soil, and every spring I fail. What little sprouts, the mice eat. It’s frustrating. I really want to raise more of my own food, so I stick with it.

Right now, it still contains a portable coop I put in there last summer, while I was fostering some cock Araucana chickens before slaughter. As soon as they started to mature they attacked my neighbor’s Brahma hens, so I moved them over here. Note the top cover of baling twine, which seems effective against raptors. The fencing works against visiting cattle and elk, both of which have devastated my garden at different times. But it only seems to encourage mice and rats.

Next spring I’ll try again, and probably fail again.

Which brings me to the final principle …

Semper Gumby! (Always flexible! Also known as “Embrace the Chaos.”)

The road to a simple life has proven very complicated indeed as the years pass. It’s not at all what I was raised to expect. City life — that is, most people’s lives — is really very rigidly controlled. Heat and cold can be softened and made comfortable with air conditioning and heating. Water runs limitless from the tap, clean and chlorine-scented. The lights always work. Everybody always knows what time it is. The days are divided rationally between weekdays belonging to your employer and weekends belonging to you. It’s all very comforting, very controlled. Predators don’t challenge your pets and threaten your livestock; rattlesnakes never show up in your yard.

Life in the boonies isn’t like that. Life in the boonies can be routine, sure, but the next emergency is always waiting. You can go nuts trying to control everything, because nothing is ever really under control. At best, it’s just handled for the moment. And although you always want to be ready to handle bad stuff when it happens, there’s really no point in worrying about it. In fact, most of the time it’s kinda fun.

The trick is to prepare for bad stuff to happen to the extent consistent with your resources and good sense, deal with it when it happens, be prepared to learn from your mistakes in failing to adequately deal with it, and not let it get you down. A sense of humor helps a lot.

We have some pretty extreme weather swings here, and they can have a serious effect on infrastructure in ways it isn’t always possible to anticipate. Some things, like solar power, you can just do without until it comes back. Other things like water are less optional. So it pays to have a plan B. And a plan C, and so on.

I’ve made some serious mistakes. During my first winter in the cabin, a free home-made and badly-designed wood stove and a lack of knowledge about the chemistry of juniper and cool, smoldering fires caused a chimney fire that almost cost me everything I’d built. So I saved up for a proper stove and I’m a lot more careful about the stovepipe. Two summers ago a combination of dehydration and the very hard water we pump out of the ground here put me in a clinic with kidney stones and nearly nonexistent blood pressure. I’d gradually gotten so tired of the texture, never mind the taste, of the local water that I’d unconsciously stopped drinking water almost entirely, and then ignored the symptoms of serious dehydration. Now I pack in all my drinking water from filter machines available in the closest town, and I monitor how much I drink.

There have been times when I needed to fall back on the help of others, and I do confess that was never in my plan. I take no state welfare, and I’m uncomfortable with charity. I do get quite a lot from neighbors, but always try to give as good as I get. Sometimes, though, in a barter economy the line between commerce and charity can be a bit blurred. We had a lengthy discussion about this on my blog during my blindness scare. If you’re providing a free product that other people can use or not, as it pleases them, and then you have a serious need and a whole bunch of them kick in a little to help you through it, is that charity? I decided I’d just call it reciprocity, which is a sort of commerce, and accept it with gratitude. I do enjoy being able to see out of my eyes.

Life in the boonies is an endless learning opportunity, and it never bores me. It’s hard sometimes, and sometimes complicated. But I love it anyway. This is where I belong.

Nice work, I spent a lot of time in my childhood living sparsely in the mountains and the desert. A good experience, but maybe one I’d rather not do again if I didn’t have to.

Too bad your marriage didn’t work out, I don’t know if I’d be able to survive without my wife. I love her dearly.

Also I wanted to know if you needed a King James Bible, you didn’t mention anything about God or Jesus. I would be willing to send you one if you wanted one.

Super great what you are doing. What area of high? desert are you living? I’m use to how it was when a kid in the 60s. People used a homestead act where you would get land free but had to build a small square building.

Please reply.